Podcast summary

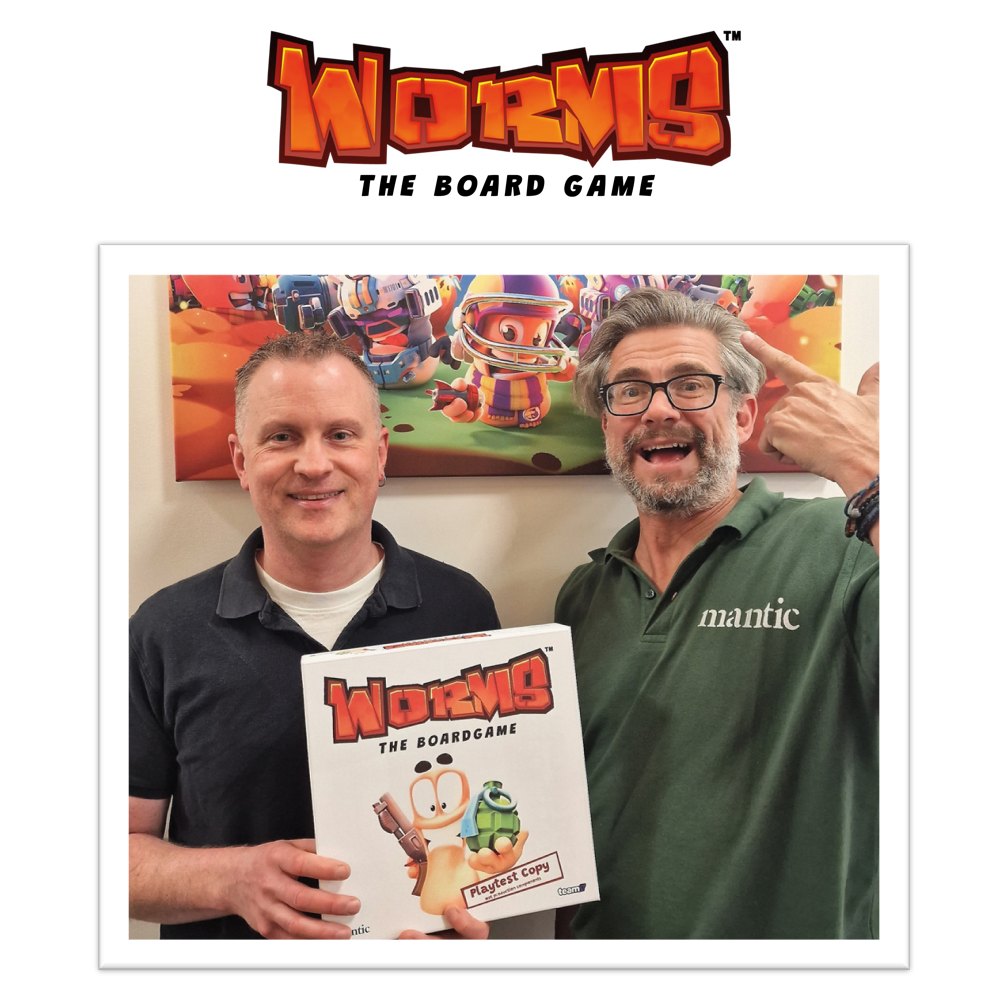

Join us as gaming industry veteran Ronnie Renton shares his rich history in the world of tabletop gaming, the ins and outs of acquiring licenses, and the secrets to Kickstarter success. From Mantic Games’ origins to acquiring popular licenses like “The Walking Dead,” Ronnie delves into the complex relationships between creators, licensors, and the community. In this enlightening conversation, Ronnie offers sage advice on crowdfunding, emphasizing the importance of engaging with your backers as more than just a source of funding. Plus, get a sneak peek into Mantic’s upcoming project: a thrilling board game adaptation of the classic video game “Worms.” Whether you’re an aspiring game creator, a seasoned entrepreneur, or a gaming enthusiast, this podcast is a treasure trove of industry insights.

Check out Ronnie’s latest Kickstarter page for Worms here, Mantic Games’s website here and follow them on X here.

Full transcript

George:0:01

Hi there. My name is George and I help independent creators launch their products and games. On this podcast, those creators share their journey from an idea to an actual product and everything in between. Today’s guest may be the most successful European Kickstarter creator of all time. He has raised more than$11 million from over 76, 000 backers combined with his company, Mantic Games. Welcome, Ronnie Renton.

Ronnie:0:28

Hi, thanks, george. Hello, everybody.

George:0:31

That’s no small feat being one of the most successful European Kickstarter creators of all time. So we’re definitely going to dive in and find out how you did that. But for those who don’t know you, what is Mantic Games and what does your company do?

Ronnie:0:44

Okay, so Mantic Games is a, gaming company, but tabletop games not computer games. It’s based upon and it started out and still has at its core DNA the collecting and painting and gaming with miniatures. As we’re now getting a little bit bigger, we’re branching out into some other licenses, properties that might not include miniatures, but often where we’ve already had the miniature license for it, say Hellboy, where we’ve now gone on and done a role play game and a card and dice game. But yeah, at its heart, I was a Warhammer fan when I was a kid and I worked there for a number of years and then realized there was opportunities in the market to combine licenses and IPs I love and ones I wanted to create with an audience that, that was hungry for those kinds of things.

George:1:33

You are coming out soon with a game based on the 90s computer game classic, Worms. We’ll get to that in a second. So that’s where your company currently stands, releasing these. incredible games based on licenses sometimes originals, but let’s go back to the early days. I was looking at your LinkedIn. You were the global marketing director at games workshop. Now, for those of you who are listening or watching and are not into games. Even if you’re not a board game person, you’ve walked past one of these stores where they sell Warhammer and miniatures and paints. What was it like in the nineties being global marketing director at Games Workshop?

Ronnie:2:18

Okay. In the nineties, I was there, I was one of the sales directors doing different markets. But it was a time of real great fun. It was going from being a 10 million to a hundred million pound business. So every week and every month and every day was different. And then latterly, what they found was that the studio made great products, but they weren’t thinking about anymore how they marketed that to a global audience, both internal and external communications, the types of product they were making. And so between 2000 and 2005, that was when I was the global marketing director. And what I was bringing was the passion that I had as a hobbyist, combining with the experience that I had as sales. And I’ve done an MBA at this point as well to make sure that the business aspects of the product development met up with the business needs of the sales divisions. The UK was no longer, while it was the largest market, it was by then only 30% of sales. So it was an international global company by this point and making sure that they had access to the same information that the UK did. Making sure that the marketing was just as relevant globally as it was locally was the challenges there.

George:3:36

What were some of the biggest lessons you learned working at such a massive gaming company about running these gaming businesses at scale?

Ronnie:3:45

I think some of the big things were, what could be sorted out quite quickly when you’re a small company, which is things like logistics becomes a major problem when you’re a big company. So what can take a week, we can all go down and pack for a day. Let’s all help them out. Turns into out of stocking products for six months. And it’s costing tens of millions of pounds worth of sales. The global nature of the product was interesting, we’d all been conquered as kids, those games workshop stores along the street and you went along and you started collecting miniatures when you put those same things in Spain or in France or in Italy or Germany at different speeds, but, they eventually started building up their own following and their own fan base. And then what was most interesting was that 80% of the sales are going to come from 20% of the lines is so hardwired. And one of my final projects was reformatting all of the stores and and how incredibly accurate that 80/20 rule is. And so no matter how big you are, we’re just doing an at Mantic now, we’re going back and looking at the range because we’d come from a smaller place, the range had spread, it had got big and unwieldy and hey, I need this figure, I need that figure, but you know what, you’re going to get 80% of your sales from 20% of your lines and make sure there’s there what’s presented well and explains well because people are always looking for new things to start and that’s, find out your core sellers and look after them, nurture them.

George:5:16

You come out of Games Workshop, a decorated career in gaming, and for some reason you decide to branch out on your own. Yeah.

Ronnie:5:27

So I evaluated some business opportunities. There’s one that I specifically left for. The games workshop had gone as far as I was concerned in its current guys, X growth which is what happened for the next seven years. It stagnated at 120 million. The only variation was the exchange rate. So I’d stopped learning. My MBA was heading into the distance. I’m mid thirties now, late thirties. If I don’t do something now, I’m not going to do it. And that was going to be my journey and my life. And that wasn’t quite what I signed up for. If games were to continue to grow, if there was challenges there, if there was some interest in in tackling new things, but, the chief exec said I want my dividends and that’s that. I was ready for another challenge. There was half of me thought, let’s go and do, I’ve done, Games Workshop became corporate. It wasn’t corporate when I joined it. It was a 10 million pound company. It had taken some VC funding, but it’s very aggressive, entrepreneurial dynamic. It’d become corporate, but I’d grown up in it. So I wondered whether I should do a corporate thing. And then I just looked at the marketplace and I just thought there was an enormous gap for Pep, Pepsi to Games Workshop’s Coca Cola, crudely, and I knew it couldn’t be as close as Pepsi and Coke, there’s a whole generation of gamers that are now coming to gaming and and in some ways, I think we’d have probably been better suited if Kickstarter hadn’t come around because it, we had one, one access to one thing and some of the others didn’t because of my MBA, I knew how to raise funds. And so we were quite a well funded company and so probably could have scaled up, but actually Kickstarter has given access to everybody for funding. But I saw a market opportunity. I thought if I don’t try it now, I’m never going to try it. And so let’s have a go at it. And that’s what we did. I probably would do a lot of things very differently. I had done a. A course on my MBA, London Business School, talking about how you fund this the startup company and this, that, and the other. I broke every single rule, every single thing that they told me not to do, I did and I did wrong and they were right. Do your studies kids and listen to your teachers. But yeah, we I saw an opportunity. I thought if I don’t do it, I never will.

George:7:40

I assume that in your MBA, they did not go to extreme lengths to talk about how Kickstarter works exist and how

Ronnie:7:47

crowdfunding works. When I did it, it didn’t exist. The only funding you could get was equity funding and it was angel investing. Banks weren’t interested 2008, 2009 too. So there was nobody playing nicely with with loans or debts or anything like that. Money was very hard to come by. One of the things I’d left for was to look at buying a business. And we’d raise the equity a couple of times, but we couldn’t get the debt funding to do that. So it was a very difficult time in terms of raising funds. There was no Kickstarter. There was no product crowdfunding. It was only equity. And it was a, pre crowd cube. So even those crowdfunding sites didn’t exist.

George:8:27

And what made you decide when Kickstarter came around, what made you decide to then go ahead and use Kickstarter, this nascent technology at the time?

Ronnie:8:35

We’d tried a few products, started to find out which ones were working. And I actually had a game coming out called Dreadball. And Dreadball, I knew was, we’d had time enough now to make the game, make the miniatures, the gameplay was very sharp, the art was sharp, the sculpting was very good. I knew it would be a successful product, coming from where we were coming. And I’d seen somebody, a company called Cool Mini not do Zombicide. Anyway, they’ve done this thing called kickstarter. A few other people have come to me and they’ve done little bits of MDF to do some terrain and they’ve done$20,000 or$30,000. And that’s what we were doing on the web at the time in a month, and our sales were probably only double that. And so we were returned$40,000 a month,$20,000 direct,$20,000 through our partners. And This kickstarter going on. So one night when I couldn’t sleep and you worry about paying the bills and everything else, I just went on and looked and just looked at all these different projects that were on there. And I thought this is what we do. We make great products and we sell them. And what this is saying is help us make great products. And just recently I’d just done the basic set for Dreadball and it was looking like we were going to make the miniatures in metal. The charm of metal is there is no upfront tooling cost, but there’s no economies of scale. You just hand pour them. And it was the medium of choice back in the 2010s. If you’re having a low volume of something and the numbers just weren’t quite there for plastics at the time. Plastic tooling was really expensive. The quality was hit and miss depending on where you were using. And I thought if we put this on Kickstarter, we might be able to just get the tooling money we need to make these. in plastic and if we can make them in plastic we can then really get that game out there and make it a huge success. And I’d already designed it for a trade release. The product was designed for a trade release and the way it’s coming and the ways and everything else. So we were just about to bring our Kings of War product to market which was our kind of core war game. And we just, we’re about to send it off to print. And I thought I’ll tell you what, I’m going to put that up first. See what that does. And then I can learn my lessons. Or if not, for Dreadball. Because I think Dreadball can be really successful on Kickstarter. And therein the problems begin. Because… As I said, we were doing$20,000 on web a month, and I thought we would maybe do$20,000 or$40,000 on Kings of War, and we did$350,000 on Kings of War. So the good news is all of this cash started coming in, and that was great. The bad news was, of course, we’d now made a load of promises that we hadn’t really planned on fulfilling. We didn’t know how we were going to fulfill them and what the problems were. And we were only eight weeks away from doing it again with Dreadball. And boom. So we went back with Dreadball three months later because that was all designed and ready. And that did$750,000. So now we’ve got two big projects to deliver. We’ve got all this cash coming in. We’ve got a relatively small team, so that’s nice and probably the right size team for a project of that size. But we’re now. On the back of the horse is running at full pelt and we’ve got to start delivering and making and getting on with it. It was hugely exciting. It was very we were absolutely at the cutting edge. Kickstarter is not very old at this point. I think we’re talking 2012, maybe. So I don’t know how old it is. We were early, early on in the cycle. And it was a wild, crazy three year ride. From putting it on there, getting the fans to talk to us. We were always community led. We’d always given our rules away free. We’d always ask for input to suddenly going from doubling, tripling overnight and then having to deliver that. And that was where we delivered it. But, boy, oh, boy, did the shipping companies do well out of it. Boy, oh, boy, did the tooling companies do well out of it. Sales is vanity. Profit is sanity and cash is reality. We had three years of vanity and we were there and we were big. The profit… We were just about saying, but all of a sudden, three years in, we realized that that the cash situation was going to be a same thing that really needed managing very seriously. And it’s that catches out and has caught out a number of the other

George:13:04

Yet you then proceed to do it all over again, not once, not twice, but about, 20 odd more campaigns. So something must’ve been working for you.

Ronnie:13:14

Yeah. I think the first six or seven were that wild ride. And what I then realized was that we didn’t have a sustainable business model. We either needed a team of four people and a large group of freelancers and we outsourced everything. Or we were going to go back to our long term roots of building a sustainable month in month out global hobby that people picked up and bought and painted. And the Kickstarter was going to be either a way of getting us the marketing and the kickstart we needed for projects, or it was going to probably be a successful marketing tool for certain projects. But what it was not going to be was the lifeblood. of the company. And the problem was we were getting to a size that two bad kickstarters and we’d be bust, and there’s a number of companies, big and high profile ones that have got into that invidious position where the next kickstarter needs to be big in order to pay for the last one, because they’re slightly overinvested. It’s very easy to run with higher overheads. And you have to be very careful that you’ve not got carry. And that you’re looking at each project and each year as it’s going to be, not as you want it to be the most dangerous words of all, you’re not, you’ve not got a hopeful business plan.

George:14:32

Yeah. Yeah. So it doesn’t inadvertently turn into a pyramid scheme of your own making that that you need to continue filling.

Ronnie:14:39

And we’ve seen a number of those. And it was it was when I realized that we were depreciating our tools over four years. Because that was standard. We’d actually speeded it up when we first set up. It was eight years because, obviously over time, but we depreciated them over four years. Yet some of these tools we were running once. The Kickstarter was the sales. We ran them for that. We ran them for the trade launch, particularly board games, and that’s it. So it’s not a four year asset. It’s a one year asset. What does that mean for your cash? Because of course, if you’re carrying three years of depreciation, so 75% of the tool value of let’s say 300 grand of the tool value, let’s say 400 grand, that makes it easy. You’re carrying 300 grand’s worth of nominal profit, but there’s no cash there. What are you going to do? How are you going to, it’s not going to help. So it was a real revelation. That’s when, and I think dungeon saga. Was the one where I said, okay, let’s just turn this on his head. Let’s sell lots of stuff, but let’s not spend lots on tooling here. We’ve got a little bit of carry and more importantly, we need to be making products they’re going to sell for the next five years. And Dungeon Saga was that product that had a great Kickstarter, superb Kickstarter. But it went on to be translated into French German. Spanish. It’s sold for the next one. We’ve literally did the last print run last year when we’ve decided to upgrade it and update it and to bring it back afresh. But it went on and had eight or nine UK English language print runs and three foreign language print runs. So we were now starting to put products into the market. We’re going to sell sustainably for a long time.

George:16:19

So is that your secret to profitability? You release a game you have the tooling costs and that’s that, but by translating it, bring it into other markets, your tooling costs aren’t going to change but you can continue to generate revenue from that game.

Ronnie:16:33

Correct. I think that is our business plan. And it’s one that I’m interested in doing because of the sustainable nature of a miniature gaming market. And we have this legacy with Kings of War that is a, which is now a brand. It’s a globally played game. It’s growing. We want to grow it more. So we’re committed to the. To the longevity route of month in, month out sales and channels as opposed to a small, neat, tight team that comes in, hits it, but you’ve all got to, you’ve all got to have some skin in that game. And was everyone else is saying you know what, you just pay me to do a job. I’m turning up to do this job, but it’s harder now than it is here because of the Kickstarter is good. You’re all happy and hey, there’s money coming in. And then if the Kickstarter is bad, and it’s very important that you. You either have a team approach that you say, we all benefit from this, or we don’t, or you’ve got a sustainable, more normal business model. And then, and it’s quite hard to have a foot in each camp. So if equivocally people ask, I would like my business to be at breakeven without any kickstarters, that would be the ideal holy grail.

George:17:38

Fast forward to today, we’re about 10 years later now, what does the company look like today?

Ronnie:17:45

So we just go through a little bit of a transition. We’re hitting that 30 staff level, 25 staff, which is where under 20, I think, and I think that, the reading supports this. It’s one team. One team doing one thing, you can all pull together going into the pandemic. We were there and we were just slowly managing this transition into a department head team where the teams needed to talk, but I was getting out of the day to day and then overnight everything changed. And what happened was that the hierarchy kind of collapsed. The release schedule, changed. There’s no point selling things if the stores aren’t open. Sales flipped online. And then coming out of that has been really quite a difficult transition because all of our attention was on ops. Sales were easy because everyone was sat at home. We were running kickstarters that I would have thought would do$100,000 did$500,000. At the time, you don’t think of it, you say it’s Hellboy. Of course, it’s going to do. Oh, yeah, of course. We’re brilliant. We just know what we’re doing. We know our customers, not they’re sat at home with absolutely nothing else to do and nothing else to spend money on. And so they’re going to give it on board games. So we’ve got sales maintained. But our operations were a challenge. So my efforts were, the cost of a shipping container went from$2,000 to$20,000. So something you’d forecast cost 10 times, which is, and that’s one of the significant, inputs into your project, particularly at the end of the project, when you spent all the money on the tooling and buying products, you need that money then to ship it out. So we’re now 30, we’ve got a US sales team. We’ve got a UK and European sales team. We’ve got a marketing team, including a full time Kickstarter manager. Who can then. It’s conceived because there’s the logistics of a campaign. You’ve got building the crowd before, getting the assets ready, making sure that operations are new. When operations, when we’re designing a game, things get dropped, they get added, they get changed, they get tweaked. If you put a picture up of the something that got dropped two iterations ago, and everyone’s then expecting that in the Kickstarter, it’s uncomfortable. So you’ve got to be on top of it. After the campaign, pledge managers, okay, we know you’ve given us a hundred dollars. We know your name is George. We know your email. That’s it. What do you want your hundred dollars? Where do you live? What tax are we going to pay for you? Do you want to add anything else to it? You need to pay for your shipping. That’s different for everybody. So there’s a whole load of logistics in, logistics out. Having those done. The marketing team then can concentrate on whatever is that month’s hot release. Of which only Kickstarter. So yeah, we’re all talking about Worms. Worms is dominating the story. But next month. We’ve got the biggest Kings of War tournament the world’s ever seen. We’re going to have 150 crazy guys in Nottingham playing with thousands and thousands of little plastic and resin men. They spent all year painting them and building them and playing them. They’re going to be playing five games over a weekend, probably drinking some beer. And and, we’ve got an advent calendar coming out that’s going to be the first ever miniatures gaming advent calendar designed for Dungeons and Dragons. Harking back to our own hobbies and it builds into a barroom brawl game. So you’ve got your dwarf and your elf and your ranger having a fight in a bar. I’m trying to get beers back to their tables. So we’ve got some really fun things coming up, and they’re just coming up one after the other. A large 16, 000 square foot warehouse with a full time team in there, casting resin, packing boxes, shipping products. So we’re at that kind of interesting stage where if we could just kick on a little bit we’re at that 30, hopefully going on to 40, 50 staff. I’d like to keep the team as small as possible. to tags as possible that’s a payroll to make every month, we’ll be making that dependent on the next Kickstarter.

George:21:39

So you said casting resin. So you make your miniatures in house?

Ronnie:21:42

Yeah. So we originally started as a plastic company and then realized that we needed a wider range faster. So we started making metal. Overnight realized that we were a very small plastic company and already quite a large metal one. We put resin and metal in kickstarters and the joy of it is you get them 12 months to make it. So you just schedule it. And then when there was a gap, we could release something else. And then during lockdown, everybody finished their armies. Everybody started buying those models that always wanted. So we had two teams working, 16 hours a day, hand casting resin, packing it up, adding the plastic into the boxes and doing all of this. Yeah, so metal became resin. It’s just a better material to work in. It’s more detailed it’s lighter. So it transitioned over. We are now managing finally, we, we’ve done some Kickstarters and not put any resin in it. We’re, winding that back down because, we’re a plastics company really. We wanna be making them in a sustainable way. But yeah we do everything. Which drives everybody mad because of course it’s it’s very complicated. And if just one piece is missing, we have to go and send it back out to everybody and ship it out all around the world to get that piece fixed.

George:22:53

That has always seemed to me like a really big financial risk in game kickstarters, because sometimes you see in the comments, folks say I’m missing this piece or I’m missing this one miniature and just the shipping costs alone of replacing one piece probably diminishes the profit on that entire order.

Ronnie:23:10

If you have a single Kickstarter wrong, it probably goes from, if you’ve got your numbers profitable to break even. It’s that dramatic because getting it, packing it, picking it, finding it, shipping it, it’s difficult. If you have a systemic error, you’re in very serious trouble. And the one thing that I talk to the team about is, checking and checking and checking before it comes out of China, checking before it arrives, checking it once it arrives. And they all look at you like you’re an idiot. And we’ve probably had six systemic errors. And those have all been the most financially painful things to fix. Often, if you’ve got good suppliers or good partners, they will share some of the pain, but the best you’re going to get is they’re going to share it. They will reprint that thing that has the page upside down. But you’re going to have to ship it. You’re going to have to then ship it out to customers, and that’s when you have to go along and say. I’m not shipping this to you until I’ve got this replacement part because I can’t afford to send 2, 000 copies of the game and everything else and all of it with it and then 2, 000 books. And in the early days when we were running too fast, we weren’t able to slow the machine down sufficiently to say. We’re going to hold the kickstarter. We’re going to hold the trade release and we’re going to, so it was great fun. It was exciting, but it was draining. It was hard work. And, the challenge for me is to make sure that we are as an organization doing everything perfectly first time in a sensible timeframe.

George:24:44

So let’s talk about IP, you have some amazing licenses. This is core to your business. You’ve done Hellboy, you’re coming out with Worms. When you were still. An itty bitty baby company. Now it must be easier. How do you go about acquiring that IP?

Ronnie:25:04

Partly why I designed our own IPs first was to ensure we had the infrastructure to deliver when we were making promises to bigger companies. We had a tooling manufacturing, we had sales channels, we had routes to market and a sales team. All of those things were already underway. And then actually, I knew we were going to do it at some point, but then the Kickstarter had really got us going. We were doing our own IPs, one after the other. And then someone at Tots called me and said, do you want to have Mars Attacks? And I was like, Oh yeah, that’s fun. Let’s do that. And I thought it would be a great way, because it wasn’t a particularly big license at the time, I thought it’d be a great way for the team to start interacting with licensors, because that’s a whole new management skill. But we had the others, we had the ability to deliver kickstarters, we have the ability to make games, we have the ability to sell those games. So it was just one additional skill set, which is dealing with the licensor, which is challenging. And if you think it’s not going to be you’re missing that they are a major stakeholder and that’s their IP. They care about it probably even more than you do. Then once we’ve done that, I got it out of the way and digested it and understood. I said, okay, now we’re ready to go onto the next stage. And then I literally got on a plane, had someone that knew a lot of people, met him for lunch. And after the end of the lunchtime, he’d given me a number of phone calls. I started making some phone calls from LA, got over and met a guy called Sean Kirkham who was at Skybound at the time that had the Walking Dead license. He’d been a Warhammer player when he was a kid. He actually sat to me when in the office, I said, Are you running a Kickstarter right now? I was like, Yeah, we’re running Dungeon Saga. He’s Holy crap. I was looking at that this morning. I was with me and my friend. We’re looking at backing that. So it felt like a little bit of fate and we managed to get a deal. We managed to do the kickstarter and we managed to get a great trade launch, which was always a long term plan with that. It was going very well. And all of a sudden, then you can start going to licensing expos and you can go to, BLE in the UK. And when you say, Oh, I don’t have any licenses or I have Mars attacks, they say, okay, tell me what you are. When you’ve got the walking dead at the prime walking dead they say oh sit down do you want a coffee would you like a glass of water we can talk so you know what I’m gonna say the first one is the most important one getting one that has some kind of license to allow you to get in the room to be taken credibly or to have a very thorough plan you are gonna be dealing with people who are serious Players, if it’s an IP that you want, other people are going to want it.

George:27:46

And how are these deals structured? Do you pay a certain fee upfront to secure the license and then a royalty? How does that work?

Ronnie:27:53

Usually there’s an advance and that is directly proportional to the size of the opportunity and the proven nature of the opportunity. So I think if you’re turning up to do duvets and pajamas. On a massive children’s global license it’s probably impossible because it’s already gone. And your, Primark will have Ben 10 pajamas and t shirts. And so whereas if you’re asking them to do something that’s cutting edge or novel, or it’s something that may be of interest to them. It’s a contractual negotiation. It’s Lawyers and checks and all those kinds of things that you’d expect to to be able to make sure that it’s going to work.

George:28:41

You’ve done this successfully multiple times. You’re coming out with another licensed game, which is Worms, which we’ll talk about in a minute. So for you, it has worked out, but would you recommend this to beginning creators or people thinking about their first campaign and then thinking about doing it with a license?

Ronnie:28:56

It perhaps depends on your background, but the ones I’ve seen being successful. If you need to prove your product concept, I’d probably try and make sure that’s proven before you start bolting it onto a licensed property. If you’re a games writer and you’ve never written a game before and you’re going to come out with a game straight off the bat with someone else’s property. Okay I’d say that’s quite brave, possibly, and it’s a very good question. It’s dangerous. I don’t want to generalize, but I think you have to be very conscious of the unknowns. The unknown unknowns. And if you promised something and I’ve seen many Kickstarters, good Kickstarters, good products, getting trouble from the contracts. I remember one where they’d agreed that they were going to pay X royalties every quarter. He did the Kickstarter and then said, great, I can pay you all year in one go. And they said no. If you pay that in one go, that just goes against that. I want the same check next quarter. I said, okay, I’ll deliver the Kickstarter in four waves. One every quarter. Because they weren’t prepared to negotiate. He just said, okay I’m going to gain the system now. What that did was drive the backers absolutely crazy. But the financial implications of not being able to gain the system was so severe for him that he would be bankrupt because he wouldn’t be able to meet the future payments because the contract said four quarters of x and and they wouldn’t change the terms or should I care so you know you’ve got to be very careful there that there’s a clause in that contract that all be negotiated away. It is a fast route to get yourself noticed and get up there, but you’ve got to be careful that you’re not just dealing with your own unknowns, you’re dealing with your own risk. And that’s.

George:30:50

Yeah, It could be to get yourself known really fast for better or worse.

Ronnie:30:54

Yes, correct. You’re taking an additional set of risks, but it comes with it, huge opportunities. If you’ve got something innovative and clever, particularly if it’s around the IP and I think backers are reasonable if you know what you’re doing, what’s the tooling cost? What’s the production costs? What’s the shipping costs? How may they change? What extra support are you going to need? And and my other word of advice is I pay the, so I can’t recognize the sales until I ship it. When I ship the Kickstarter, I recognize the sales. That’s what’s gone out the door. That’s what I report to the taxman. Now the taxman being very nice, takes the 20% VAT straight away. He doesn’t mess around. He doesn’t wait. He says, I’ll have the cash up front. And when you when you finally ship it, we can deal with the numbers. But I also pay my licensors at that point as well. When I’ve done the Kickstarter, I get their 10%, 10% or whatever their royalty fee is. I get there and I give them a big slug of it and say, listen, this is your money. And now in the time you couldn’t get any interest in your bank account. So now it’s quite nice to have it in your own bank account. But at the time I would hand it over and say, look, there it is. That’s yours. I’m going to, this money is the money I’ve got to deliver this project with. And there’s a number of licensors that have never been paid their royalties on Kickstarters.

George:32:15

Good words of advice. Let’s look at one of the most exciting licenses coming to board games in a while. You are releasing Worms. Tell us and show us everything you’re willing to share and show.

Ronnie:32:27

Okay, great. So I’m just on the Mantic page here. Can I can I show you my page? Yes, there we go. Yes. Okay. So here we are. I’ve just showing off now, the Worms, the board game update, on the 4th of August. So this is us at team 17 designed the worms game. You can see a worm down there. Back in the nineties, huge popular computer game where you basically shot the living crap out of everybody else. Who had a team in the worms and you kill their worms and have fun with each other. And there is us down. That’s the game designer, Jack and our operations director. And this is Greg from team 17. And we created a board game that recreates the kind of chaos and mayhem of the 1990s computer game. You scatter your worms around, you all have a few starting weapons, and then you’ll draw from the weapons deck up here. As you get loot, as you get crates, and these will allow you to pick a new weapons and you’ll blow up the oil drums, mines will go off, you’ll shoot each other, but in typical worm style, it never quite happens exactly as you plan. So your genius field marshal skills will will come up with the most cunning of plans, my lord. And then it will go horribly wrong because the wind will take it. or it’ll blast in the wrong area and invariably with a few little dice it’ll end up landing on yourself and blowing your own worm up. But the stars of the show are the worms and these are some of the little sculpts we’ve done and it just gives real character and real fun to your games so that you can, you put your little color counter up and pick your own team and and off you go. So who doesn’t remember these and love these? And that is coming to Kickstarter. In late August, about August the 22nd. And yeah, come join us. It’s going to be a fun ride. Every single day we’re going to be adding extra things to the pledge. So it’ll be good value on the first day and extremely good value by day 17. This is because the more help and the more support we get, the bigger the campaign will be. And we want to pass those savings on to our on to our fans.

George:34:34

The link to this will be in the show notes of this episode. So if you want to get your worm set, click in the link in the show notes, it will be there. Ronnie, thank you so much for sharing your rich history in the world of gaming entrepreneurship and still being super active and coming up with amazing things like worms. Do you have any parting words of wisdom for aspiring kickstarter creators that you’d like to share.

Ronnie:35:02

No, I think the key words that I’ve said, and a few times I’ve been asked to talk about it is the the clues in the title, when it talks about crowdfunding, make sure you can tell who is your crowd. A lot of people, particularly if you come with your MBA training and your business, you think about the funding, you think about the numbers, what’s in it for the crowd, where are you going to find them? How are you going to talk to them? And I think if you can do that, then you’ve got a very good chance of a successful crowdfunding project.

George:35:29

Ronnie, thank you so much.

Ronnie:35:31

Thanks, George.